Leaf Anatomy A Complete Guide to Structure and Function

Leaves are the primary organs of plants where most photosynthesis takes place Plants show an incredible variety of leaf forms but their internal design follows common principles that allow gas exchange light capture and water balance Understanding Leaf Anatomy is essential for students gardeners and nature lovers who want to connect structure with function In this guide we examine the main tissues cells and features that make leaves efficient energy collectors and we show how these parts work together

Why Leaf Anatomy Matters

At a basic level the study of Leaf Anatomy reveals how plants convert light into chemical energy While surface shape and size influence how much sunlight a leaf can absorb the internal arrangement of cells determines how effectively light is used and how gases move in and out of the leaf Leaf Anatomy also explains how plants cope with stress from drought heat or pests Knowledge about leaves is valuable for ecological research crop improvement and even for everyday gardening For curated natural science content visit bionaturevista.com to explore articles and images that deepen your appreciation of plant life

Basic Layers of a Typical Leaf

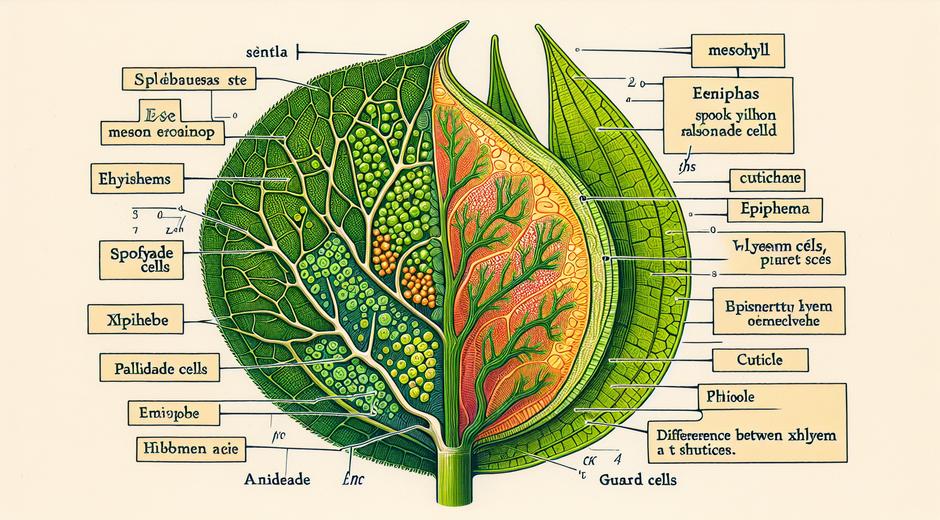

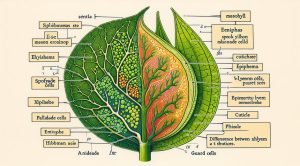

Most leaves share a layered construction that can be seen in cross section Starting from the outside and moving inward the main zones are the epidermis mesophyll and vascular tissues Each zone contains specialized cells with distinct roles

Epidermis and Cuticle

The epidermis is the outer protective layer on both upper and lower surfaces It consists primarily of epidermal cells that are tightly packed to reduce water loss Many leaves are coated by a waxy cuticle produced by epidermal cells The cuticle acts as a waterproof barrier that slows evaporation and protects against pathogens While the cuticle reduces water loss it also restricts gas exchange therefore plants use specialized openings to balance these needs

Stomata and Guard Cells

Stomata are microscopic pores in the epidermis that regulate gas exchange Each stoma is flanked by a pair of guard cells that swell or shrink to open or close the pore When stomata open carbon dioxide enters for photosynthesis and oxygen exits as a byproduct Water vapor also leaves through stomata so plant control of pore opening is a matter of balancing carbon gain with water loss Guard cell movement is driven by changes in cell turgor that are influenced by light water status and plant hormones

Mesophyll Photosynthetic Engine

The mesophyll is the middle region of the leaf where most photosynthesis occurs It is typically divided into two layers The upper palisade layer contains elongated cells packed with chloroplasts that absorb most of the incoming light Beneath it the spongy layer has loosely arranged cells with air spaces that facilitate gas diffusion This internal architecture ensures that light penetrates the leaf while carbon dioxide moves efficiently to photosynthetic cells

Vascular Tissue Veins That Transport

Leaves contain a network of veins that provide water and nutrients and carry sugars produced by photosynthesis to other parts of the plant The conductive tissues xylem and phloem are organized within vascular bundles Xylem moves water and dissolved minerals from roots to leaves while phloem distributes sugars from leaves to growing tissues The pattern density and size of veins vary among species and influence leaf shape mechanical strength and the ability to recover from damage

Specialized Cells and Structures

Beyond the basic layers leaves may contain many other specialized cells and features Trichomes are hair like projections from the epidermis that can reduce herbivory reflect excess light and trap moisture Some leaves have thickened cells or sclerenchyma fibers that add rigidity Others develop glands that secrete substances for defense or attraction of beneficial organisms Adaptations such as sunken stomata thick cuticles or multiple layers of palisade cells are common in plants that live in arid or high light environments

Internal Transport and Water Relations

Leaf Anatomy supports fluid movement at multiple scales Water delivered by xylem flows into leaf cells and evaporates into air spaces before exiting through stomata This process known as transpiration creates tension that pulls water from roots to leaves It also cools the leaf and drives nutrient transport However excessive water loss can be lethal so plants regulate stomatal opening and may modify leaf anatomy to reduce transpiration under stress

Leaf Types and Anatomical Variations

Simple leaves have a single blade while compound leaves are divided into distinct leaflets Each type exhibits anatomical adjustments to suit its ecological role For example shade leaves are often thinner with more spongy mesophyll to capture diffuse light Sun leaves are thicker with more palisade tissue to handle high irradiance Aquatic leaves may lack a thick cuticle and show abundant air spaces to aid buoyancy and gas exchange

Microscopic Tools for Studying Leaf Anatomy

Leaf Anatomy is often explored using thin sections mounted on slides and viewed with a light microscope Staining techniques highlight cell walls chloroplasts and vascular tissue Electron microscopy reveals ultrastructural details such as chloroplast internal membranes Observations at different scales from whole leaf imaging to cellular microscopy provide a complete picture of form and function Researchers also use imaging and computational tools to quantify traits such as vein density stomatal distribution and tissue thickness which are important for ecological and agricultural studies

Development and Genetic Control

Leaf formation begins at the shoot apex where cells differentiate into leaf primordia Genetic networks regulate the patterning of leaf tissues and the timing of cell expansion and specialization Hormones light and environmental signals shape final leaf anatomy Genes that influence stomatal density vein formation and chloroplast development are active research areas because they have direct implications for plant productivity and stress tolerance Genetic and breeding approaches aim to modify leaf traits to improve crop efficiency or resilience

Practical Applications and Conservation

Understanding Leaf Anatomy has practical value in agriculture forestry and conservation For farmers leaf traits can inform irrigation scheduling pest management and variety selection Leaf anatomy also helps in diagnosing plant health issues such as nutrient deficiency or pathogen infection In ecological contexts leaf anatomy contributes to species identification and offers clues about habitat adaptation Preserving plant diversity means protecting a wide array of leaf designs that support ecosystem functions

Further Reading and Resources

For students preparing reports or seeking study guides on plant structure a useful resource is StudySkillUP.com which offers study tips and subject specific support Integrating anatomical knowledge with field observation and lab practice builds a deeper appreciation of how plants operate

Conclusion

Leaf Anatomy links structure with the vital functions of plants From the protective epidermis and the gas exchange of stomata to the photosynthetic mesophyll and the transport role of veins each component contributes to the leaf goal of converting light energy into compounds that sustain life By exploring leaf form across species and environments we learn not only about plant survival but also about broader ecological processes Whether you are a student researcher gardener or nature enthusiast a clear grasp of Leaf Anatomy enriches your understanding of the green world around you