Desert Adaptation: How Life Thrives Where Water Is Scarce

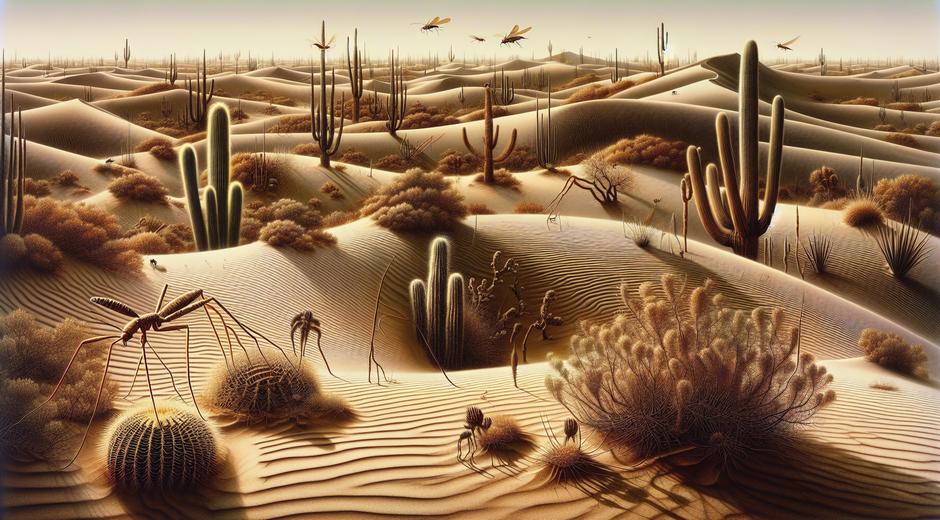

The desert is one of the most extreme environments on Earth. Daytime temperatures can soar while nighttime temperatures can fall sharply. Rain may arrive in rare storms and then vanish for months. Yet deserts support a surprising diversity of life. From plants to mammals to tiny microbes, desert adaptation reveals nature at its most resourceful. In this article we explore the strategies that species use to survive and to reproduce under heat stress limited water and scarce food. We also look at lessons humans can draw for conservation science and for sustainable living in dry places.

What Is Desert Adaptation

Desert adaptation refers to the suite of physical behavioral and physiological traits that enable organisms to live successfully in arid environments. These traits reduce water loss increase water acquisition control body temperature and optimize energy use. Adaptation can be structural such as specialized roots or fur or it can be behavioral such as nocturnal activity patterns. Over evolutionary time natural selection favors traits that increase survival and reproductive success in a given desert setting.

Major Challenges of Desert Life

Understanding the challenges faced by desert dwellers helps to explain why certain adaptations are so common. Key challenges include:

1) Limited available water. Many deserts receive small annual rainfall and water can evaporate quickly in heat.

2) Extreme temperature swings. Heat stress during daytime requires cooling mechanisms and large temperature drops at night require insulation or shelter.

3) Sparse plant cover. Food can be limited so organisms must either travel long distances store energy or exploit niche resources.

4) Saline soils and poor nutrients. Some deserts have soils with high salt content that restrict plant growth.

Plant Strategies for Desert Survival

Plants show some of the most striking desert adaptation traits. Succulence is one classic example. Succulent plants store water in thick leaves stems or roots. Cacti are the iconic succulents in many deserts but succulents include many species across the globe. Thick tissues act as water reservoirs that allow the plant to maintain metabolic function during dry spells.

Other plants reduce water loss by minimizing leaf area. Some have small needle like leaves or spines which also protect against herbivores. Many desert plants have a waxy outer layer on leaves that reduces evaporation. Deep or widespread root systems are common. Some trees and shrubs send roots deep to reach groundwater. Others spread shallow roots widely so that they can capture water from fleeting rain events.

Some plants employ special photosynthetic pathways that increase water efficiency. A pathway known as CAM allows stomata to open at night when temperatures are lower and humidity is higher so that the plant loses less water while still fixing carbon during the day. This kind of physiological adjustment exemplifies the elegance of desert adaptation.

Animal Solutions: Behavior Structure and Physiology

Animals use a mix of behavioral tricks and body features to cope. Many mammals are nocturnal. They stay in burrows or shaded dens during the heat of the day and emerge at night to forage. Burrows can buffer extreme temperatures and offer higher humidity enabling better water retention.

Some desert animals are masters at conserving water. The kangaroo rat for example obtains most of its water from metabolic processes rather than drinking free water. It has highly efficient kidneys that concentrate urine and reduce water loss. Camels famously store fat in their humps which can be converted to water and energy during extended dry periods. Their blood cells tolerate dehydration and they can allow their body temperature to rise to avoid sweating which would waste water.

Birds use behavioral cooling such as standing in shade panting or orienting their bodies to reduce sun exposure. Reptiles often use sun basking in the morning to warm up then retreat to shelter to avoid midday heat. Some insects are active only during brief cool periods of morning or evening and use reflective body surfaces to reduce heat gain.

Microbial and Fungal Adaptations

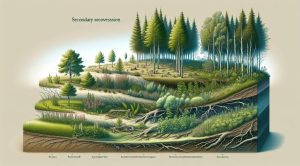

Microbes and fungi are small but powerful contributors to desert ecosystems. Many soil microbes enter dormant states during dry times and reactivate when moisture returns. Some produce protective compounds that stabilize cellular structures against desiccation. Biological soil crusts composed of cyanobacteria lichens and mosses bind soil particles preventing erosion and aiding seedling establishment after rains.

These micro scale processes have large scale effects on nutrient cycling and plant recovery after storms. Protecting these communities is important for maintaining desert resilience.

Reproductive Strategies in Arid Lands

Reproduction in deserts often hinges on timing. Some plants are annuals that germinate grow and set seed rapidly after rainfall. Their seeds remain dormant for long periods until conditions are favorable. This bet hedging approach spreads risk across time. Perennial plants may reproduce less frequently but invest in durable structures that survive drought.

Animals often time breeding to coincide with resource pulses. Some rodents and insects reproduce explosively after rain events when food is abundant. Others produce fewer offspring but provide high levels of parental care to increase juvenile survival.

Adaptation Trade offs and Ecological Limits

Every adaptation comes with trade offs. Thick waxy leaves reduce water loss but can limit gas exchange. Nocturnal activity opens new feeding opportunities but may increase predation risk from nocturnal predators. High efficiency kidneys reduce water loss but can be energetically costly. Understanding these trade offs is central to ecology and to conservation strategies.

Human activities can push desert systems past ecological limits. Overgrazing off road activity and water extraction can damage plant cover and soil structure leading to desertification. Protecting native species and their habitats requires integrated land management that recognizes the unique adaptations at play and the time scales on which recovery can occur.

Lessons for Human Design and Conservation

Desert adaptation offers inspiration for human buildings agriculture and resource use. Traditional architecture in many arid regions uses thick walls small windows and courtyards to buffer heat and to conserve water. Modern design can borrow from plant water efficiency and animal thermoregulation to develop passive cooling systems and low water landscaping.

In agriculture selecting drought tolerant crop varieties and adopting water wise irrigation methods such as drip systems can boost resilience. Restoring native plant communities can rebuild soil health and improve water infiltration. Conservation programs that protect critical water sources and migration corridors help maintain the dynamics that desert species need to survive.

For readers seeking more background on native species conservation and practical nature guides consider visiting authoritative resources such as bionaturevista.com where you will find articles field guides and habitat restoration tips that highlight desert systems and their inhabitants.

Human Health and Performance in Hot Dry Environments

Humans face their own challenges in deserts. Heat exhaustion dehydration and sun exposure are real hazards. Training professionals outdoor guides and athletes who perform in arid climates use specific strategies to maintain hydration to prevent heat illness and to optimize performance. If you are interested in sport science and recovery strategies that apply across climates a useful resource is SportSoulPulse.com which covers hydration strategies acclimation practices and gear recommendations.

Conclusion

The study of desert adaptation reveals how life finds creative solutions to limits. From water storing succulents to nocturnal mammals and resilient microbes each adaptation is a response to intense selection pressures. Protecting desert ecosystems means respecting these evolved strategies reducing human impacts and learning from nature to design more resilient systems for agriculture urban planning and recreation. As climate patterns change knowledge about desert adaptation will become more relevant for communities worldwide working to manage water protect biodiversity and to live more sustainably in arid places.

Exploring deserts with curiosity and caution reveals an ecosystem of unexpected abundance and complex interactions. The more we learn the better we can steward these fragile landscapes so that the remarkable adaptations of desert life continue to thrive for generations to come.