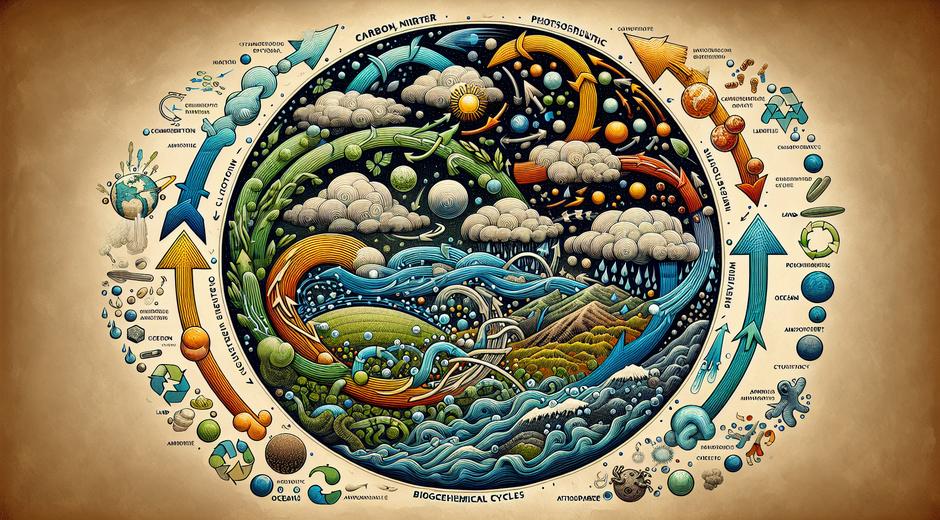

Biogeochemical Cycles

Biogeochemical Cycles are the natural pathways by which essential elements move through the living and non living parts of Earth. Understanding these cycles is key for anyone interested in ecology conservation and the continued health of our planet. This article explores the main cycles the processes that drive them and the ways humans can support healthier ecosystems. If you enjoy deep dives into natural systems visit bionaturevista.com for more articles and resources.

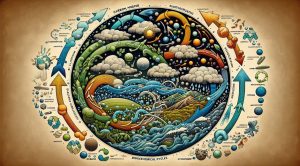

What Are Biogeochemical Cycles

At their core biogeochemical cycles describe how elements such as water carbon nitrogen phosphorus sulfur and oxygen are recycled between the atmosphere lithosphere hydrosphere and biosphere. These cycles rely on physical chemical and biological processes. For example water moves by evaporation condensation precipitation and runoff while carbon cycles through photosynthesis respiration decomposition and geological storage. The seamless interaction of these processes supports life on Earth by maintaining nutrient balance and enabling energy transfer.

The Water Cycle

The water cycle is perhaps the most familiar of the biogeochemical cycles. Water evaporates from oceans lakes and soils rises into the atmosphere forms clouds and returns as precipitation. Ground water recharge and surface runoff then return water to rivers lakes and oceans. This movement regulates climate supports plant growth and sustains freshwater supplies for animals and humans. Human activities such as land conversion and pollution alter the timing and quality of water flow so protecting watersheds and restoring wetlands is critical.

The Carbon Cycle

Carbon cycles through atmosphere living organisms soils oceans and rocks. Plants capture atmospheric carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and store it in biomass. Animals consume plants and release carbon back to the atmosphere through respiration. When organisms die decomposers return carbon to soils or it can be trapped for long periods as fossil fuels. Human combustion of fossil fuels and large scale land clearing has greatly increased atmospheric carbon dioxide with major consequences for global climate. Reducing emissions protecting forests and enhancing soil carbon storage are practical ways to support the carbon cycle.

The Nitrogen Cycle

Nitrogen is essential for proteins and DNA yet atmospheric nitrogen is not directly usable by most organisms. Specialized bacteria convert inert atmospheric nitrogen into forms plants can use through a process called fixation. Plants then incorporate nitrogen into their tissues animals eat those plants and decomposers return nitrogen to soils or emit it back to the atmosphere. Human driven inputs from synthetic fertilizers and fossil fuel burning have doubled the rate of nitrogen fixation leading to water pollution and biodiversity loss. Better fertilizer management and restoration of natural habitats help rebalance the nitrogen cycle.

The Phosphorus Cycle

Phosphorus moves more slowly than other elements because it lacks a gaseous phase under Earth surface conditions. It cycles between soils sediments and living organisms. Weathering of rocks releases phosphate which plants absorb. Excess phosphorus often accumulates in soils or runs off into waterways causing algal blooms and oxygen poor zones. Sustainable agricultural practices reduced erosion and careful use of phosphate based fertilizers are essential to maintain this cycle and protect freshwater systems.

The Sulfur Cycle

Sulfur exists in the atmosphere soils and oceans and cycles through microbial activity volcanic emissions and human sources such as industry. Sulfur compounds are important for some proteins and for soil fertility. However excess sulfur emissions can lead to acid deposition which damages vegetation and aquatic life. Cleaner energy production and emission controls reduce harmful sulfur release while maintaining natural sulfur inputs keeps ecosystems functioning.

Human Impacts on Biogeochemical Cycles

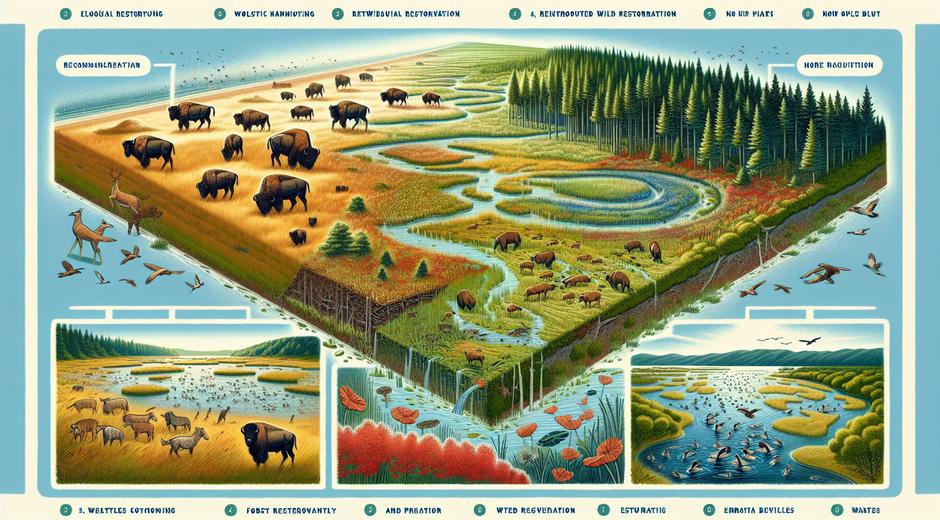

Human activities have altered the pace and balance of many biogeochemical cycles in ways that affect climate water quality soil health and biodiversity. Fossil fuel burning increases atmospheric carbon dioxide causing global temperature shifts. Overuse of fertilizers alters nitrogen and phosphorus cycles harming aquatic ecosystems. Urban growth and deforestation change water cycles by increasing runoff and reducing infiltration. These changes are interconnected so solutions often provide multiple benefits across cycles. Protecting intact ecosystems restoring degraded lands and adopting sustainable practices in agriculture forestry and urban planning are effective strategies.

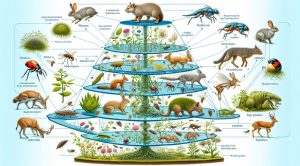

Ecosystem Services and Cycle Resilience

Healthy biogeochemical cycles underpin vital ecosystem services such as clean water climate regulation soil fertility and food production. Natural features like wetlands forests and grasslands act as buffers that absorb excess nutrients store carbon and moderate water flow. Maintaining landscape diversity and connectivity makes cycles more resilient to shocks like drought or extreme rainfall. Community based conservation and science informed land use decisions strengthen those natural services and help societies adapt to change.

Monitoring and Management

Advances in remote sensing water and soil sensors and molecular tools now allow more precise tracking of nutrient flows and storage. Monitoring helps identify hotspots of pollution nutrient deficiency or unexpected changes that require action. Management approaches range from precision agriculture that matches fertilizer inputs to crop needs to large scale reforestation and wetland restoration projects. Policymakers stakeholders and local communities play a role in setting priorities and implementing effective management.

How Individuals Can Help

Individual choices matter in supporting balanced biogeochemical cycles. Reducing energy use and choosing low carbon travel options lowers emissions that affect the carbon cycle. Using fertilizers sparingly and supporting organic or conservation agriculture reduces nutrient runoff. Conserving water avoiding pollutants and planting native species in gardens improves local water and nutrient cycling. Public education and participation in local restoration projects also magnify positive effects.

The Future of Cycle Research and Action

Scientific research continues to reveal the complexity of biogeochemical cycles and how they interact with climate biodiversity and human systems. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern science enhances understanding and yields practical solutions. Cross sector collaboration across science policy and community groups will be essential to design scalable interventions that restore balance. For examples of projects insights and resources that connect science and practical action visit StyleRadarPoint.com.

Conclusion

Biogeochemical Cycles are the unseen rivers that carry the building blocks of life across Earth systems. Protecting and restoring those cycles supports climate stability clean water fertile soils and robust biodiversity. Whether through changes in policy industry or personal behavior we all play a role in maintaining the natural flows that sustain life. Continued learning collaboration and action will keep those cycles functioning for present and future generations.