Ecological Interactions: How Species Shape Each Other and Their World

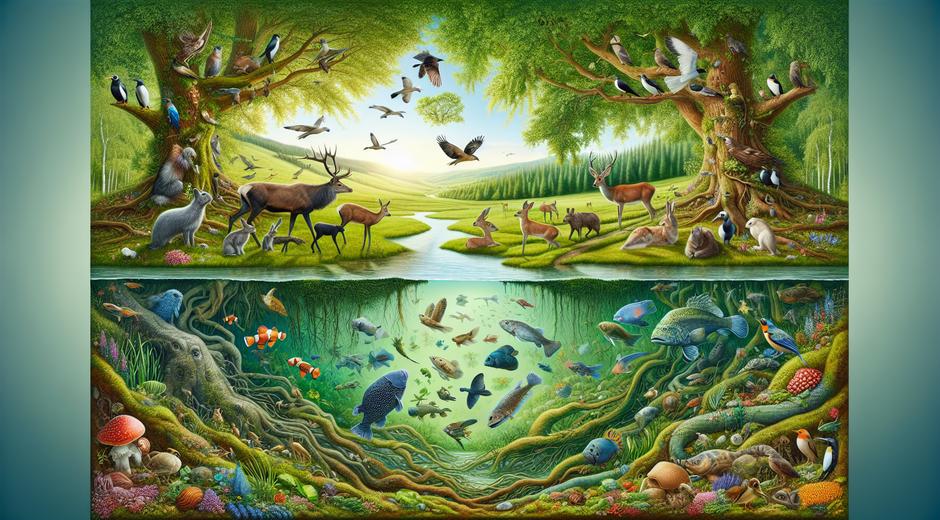

Ecological Interactions are the web of relationships that connect living organisms to one another and to their environment. These interactions drive population dynamics community structure and the flow of energy and matter across landscapes. Understanding how species interact is essential for conservation restoration agriculture and even for how cities plan green spaces. In this article we explore the main types of ecological interactions why they matter how scientists measure them and practical steps anyone can take to support healthy interaction networks in nature.

What Are Ecological Interactions

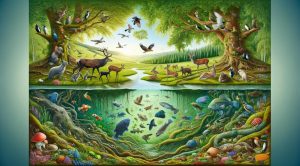

At its core an ecological interaction occurs when two or more species affect each other in a way that changes their survival reproduction or distribution. Interactions can be direct or indirect short term or persistent and they can operate at local and landscape scales. Some interactions benefit both partners while others favor one at the expense of another. Ecological Interactions include relationships among predators and prey among plants and pollinators between hosts and parasites and many more complex links that scale up to shape ecosystems.

Key Types of Ecological Interactions

Ecologists classify interactions by their outcomes for the species involved. Familiar categories include mutualism where both species benefit competition where both suffer to some extent predation where one species consumes another parasitism where one species benefits while harming the host and commensalism where one benefits and the other is largely unaffected. Less well known but equally important interactions include facilitation where one species makes conditions better for another and amensalism where one species is harmed while the other gains no benefit.

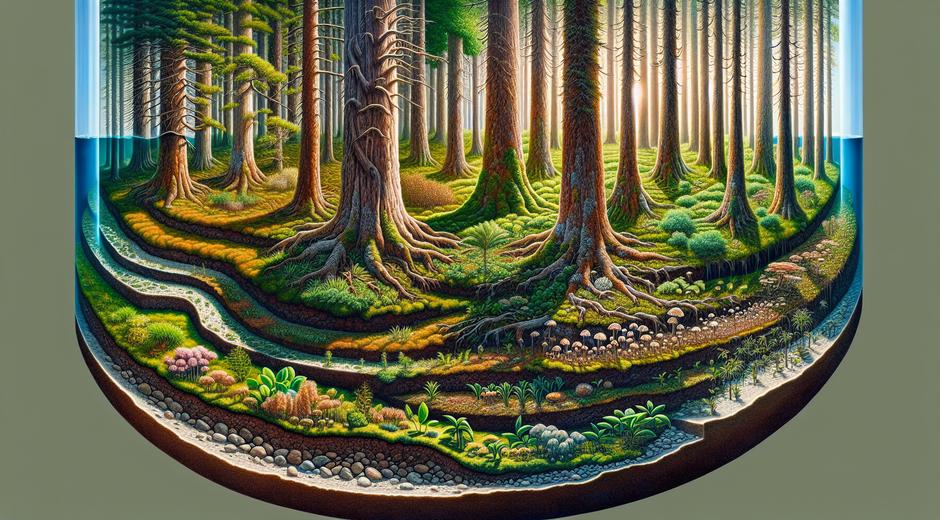

Examples help make these ideas concrete. Pollination of flowering plants by bees and birds is a classic mutualism that underpins food webs and crop production. Wolves hunting deer illustrate predation that can trigger a cascade of changes in vegetation and river form. Mycorrhizal fungi that connect plant roots are a form of facilitation that enhances nutrient uptake and drought resilience. Parasites and pathogens regulate host populations and can drive evolutionary change through selective pressure.

Why Ecological Interactions Matter for Ecosystem Health

Interactions are the mechanism by which biodiversity translates into ecosystem function. Mutualistic networks of pollinators and plants support food production and wild plant regeneration. Predator prey dynamics control herbivore numbers and prevent overgrazing. Symbiotic microbes fix nitrogen in soil and boost plant growth. When interaction networks are intact ecosystems are more productive stable and resilient. When networks are broken by habitat loss invasive species or pollution the consequences cascade into lost services such as pollination clean water and soil fertility.

Measuring and Mapping Interactions

Modern ecology uses a suite of tools to reveal who interacts with whom and how strongly. Field observations and experiments remain foundational. Manipulative experiments let researchers test the effect of removing a species or altering interaction strength. Stable isotope analysis helps map energy flow across food webs. DNA based methods such as metabarcoding reveal hidden trophic links including what predators eat and what pollinators visit flowers. Network analysis offers a powerful framework to visualize interactions and identify keystone species that have outsized effects on community stability.

Ecological Interactions and Human Systems

Humans shape and depend on ecological interactions every day. Agriculture relies on pollination pest regulation and soil microbial activity. Fisheries depend on food web dynamics. Urban design can either fragment habitat and break interactions or provide corridors and green infrastructure that sustain species movement and pollination. Effective natural resource management accounts for interaction networks rather than focusing on single species in isolation. This approach reduces unintended consequences and improves long term outcomes.

Case Studies: Interaction Driven Outcomes

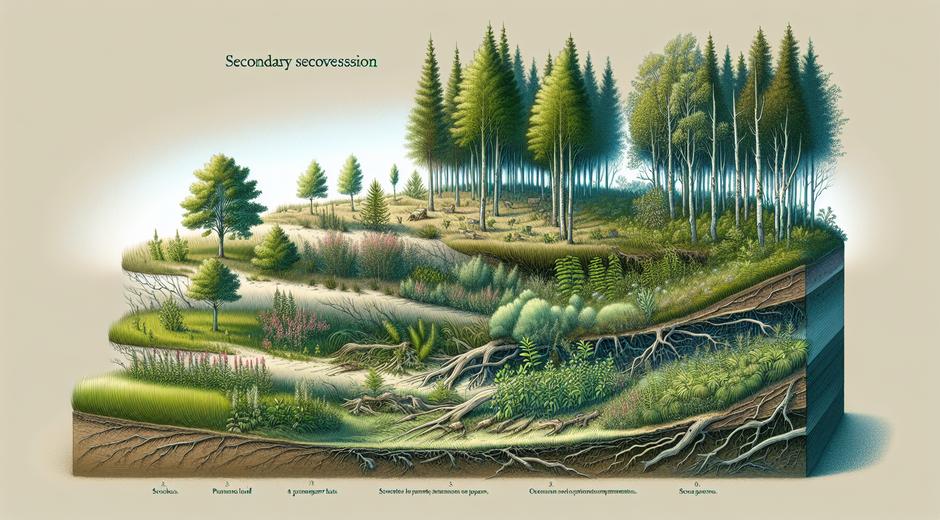

On islands invasive rats that feed on seabird eggs can collapse seabird populations which in turn reduces nutrient input to coastal plants and changes vegetation structure. Restoring seabirds reverses these changes and reveals the chain of linked interactions. In agroecosystems planting strips of native flowering plants boosts pollinator diversity which leads to better crop yields. Rewilding large herbivores and predators in some landscapes has shown how returning lost interactions can restore vegetation patterns and soil processes.

Managing for Healthy Interaction Networks

Conservation and restoration that focus on interactions aim to rebuild natural links as well as species numbers. Practical steps include protecting habitat connectivity so species can find partners for mutualism and avoid local extinctions creating refuges and corridors for pollinators and seed dispersers controlling invasive species that disrupt native networks and fostering heterogeneous landscapes that support diverse niches. In urban areas installing native plant gardens reducing pesticide use and creating nesting habitat for pollinators all strengthen beneficial interactions.

Tools for Practitioners and Citizen Scientists

Monitoring interactions can be accessible. Citizen science platforms let volunteers record pollinator visits bird feeding interactions and phenology data that feed into scientific studies. Simple experiments such as exclusion trials where a pollinator or herbivore is excluded from a plant reveal interaction strength. Smartphone cameras and community based surveys expand the reach of data collection. For those wanting deeper learning and curated content on how human culture and technology intersect with natural systems explore resources such as GamingNewsHead.com for allies in translating engagement into awareness.

Challenges in Studying Interactions

Interactions are dynamic and context dependent. Seasonality climate variability and historical land use all influence who interacts with whom. Rapid environmental change such as warming and extreme weather can shift phenology and decouple once reliable interactions like pollination. Additionally interactions can produce nonlinear effects where small changes lead to large outcomes making prediction difficult. That is why adaptive management that monitors responses and adjusts actions is essential.

The Role of Research and Education

Advancing our understanding of Ecological Interactions requires integrated research across disciplines. Field ecology genetics remote sensing social science and modeling must work together to predict system responses and design interventions. Education at all levels builds a public that recognizes the value of connected species and supports policies that protect interaction networks. For ongoing nature based news articles research summaries and habitat tips visit trusted sites such as bionaturevista.com for practical guidance and inspiration.

Actions You Can Take to Support Interaction Networks

Anyone can help strengthen ecological interactions with simple actions. Plant native species to support pollinators and seed dispersers create layered vegetation with ground cover shrubs and trees to provide diverse niches limit pesticide and herbicide use that weakens mutualisms and build water wise gardens that support soil microbes. Support local conservation groups and participate in habitat restoration and monitoring projects. Small local actions accumulate to rebuild regional networks and increase resilience to environmental change.

Conclusion

Ecological Interactions are the invisible hands that shape biodiversity and ecosystem function. From tiny microbes that transform soil nutrients to apex predators that structure landscapes interactions matter for nature and for human wellbeing. By studying mapping and managing these interactions we can design more effective conservation actions enhance food security and create cities that support life in all its forms. The more we learn to value and support interaction networks the better equipped we will be to safeguard a healthy planet for future generations.