Ecosystem Connectivity: How Nature Stays Linked and Why It Matters

Understanding Ecosystem Connectivity

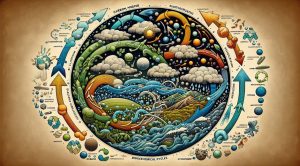

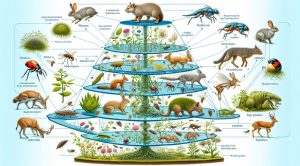

Ecosystem Connectivity refers to the ways that ecosystems, habitats, species and ecological processes are linked across space and time. It is about movement and flow. Water moves through rivers and wetlands, pollinators move between flower patches, and genetic exchange occurs when individuals travel between populations. When connectivity is strong species can access food mates and safe places to live. When connectivity is weak populations become isolated and the risk of local extinction rises. For any conservation strategy that aims to maintain biodiversity ecosystem connectivity is a central concept.

Why Connectivity Is a Core Conservation Priority

There are practical reasons why managers and planners focus on connectivity. First connectivity supports gene flow which keeps populations healthy and able to adapt to change. Second connectivity allows seasonal movements that many species rely on to complete their life cycles. Third connectivity supports the movement of energy and materials which sustain ecological functions. Protecting individual patches of habitat without regard to how those patches connect can yield short term gains while missing long term resilience benefits.

Types of Connectivity

Ecological scientists describe several types of connectivity. Structural connectivity refers to the physical arrangement of habitat patches across a landscape. Functional connectivity describes how organisms perceive and use the landscape for movement. Genetic connectivity measures actual gene exchange and demographic connectivity tracks the flow of individuals among populations. All types are related and all matter when designing interventions to improve the health of ecosystems.

Common Threats to Connectivity

Human activity often reduces connectivity. Urban expansion roads and intensive agriculture fragment natural areas. Energy infrastructure and waterways can block movement corridors. Invasive species and pollution can alter the suitability of habitats and create barriers to movement. Climate change is shifting the locations of suitable habitat faster than some species can move which makes connectivity even more important. In many places a combination of pressures reduces the ability of species to respond to new conditions.

Designing for Better Connectivity

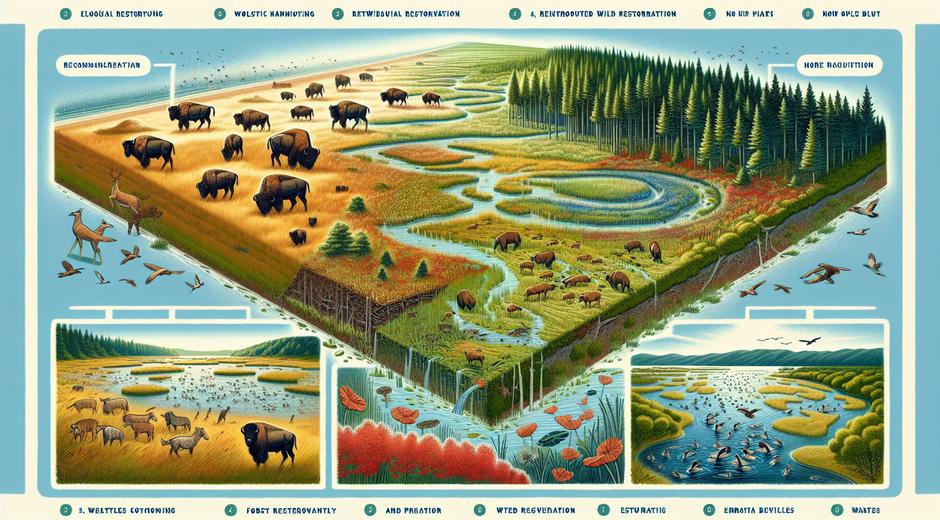

Restoration and planning can improve connectivity. Creating corridors of suitable habitat between isolated patches allows animals to move safely. Restoring riparian zones along rivers improves water quality and provides linear travel routes. Managing for stepping stone habitats on a matrix of land provides intermittent refuges for mobile species. Planning at the scale of whole landscapes and including the needs of less visible species yields better outcomes than single site actions alone.

Tools and Methods to Measure Connectivity

Advances in remote sensing and spatial analysis give practitioners tools to map structural connectivity across large areas. Movement data from GPS collars and tracking tags inform models of functional connectivity for target species. Genetic sampling reveals whether isolated populations remain connected. Modeling tools allow managers to test scenarios to see which conservation actions yield the greatest connectivity gains. Together these methods support evidence based decisions that balance conservation with economic needs.

Connectivity and Climate Adaptation

Climate driven shifts in range create new connectivity needs. As temperature and precipitation patterns change species will need to move to new areas to survive. Well connected landscapes allow species to adjust their ranges gradually and track suitable conditions. Connectivity also supports the persistence of ecological communities by enabling recolonization after local disturbances. Investing in connectivity now increases the options available to nature under future uncertainty.

Social and Policy Dimensions

Connectivity is not only an ecological issue. Land ownership patterns planning rules and economic incentives shape the possibilities for connected landscapes. Collaborative approaches that engage landowners indigenous groups conservation organizations and government agencies are often the most effective. Policy frameworks that incentivize conservation across property lines encourage the creation of corridors and networks. For news and analysis on policy trends that influence conservation practice visit Politicxy.com which covers intersecting themes of governance and environment.

Community Roles and Local Actions

Local communities play a critical role in maintaining connectivity. Simple actions such as planting native vegetation along streams preserving hedgerows and reducing pesticide use can restore movement options for pollinators birds and small mammals. Community led monitoring provides valuable data on seasonal movements and species presence. Education and outreach build support for landscape scale initiatives and help reconcile competing land uses in ways that sustain connectivity.

Economic Benefits of Connected Nature

Maintaining connectivity has economic upsides that benefit people. Connected ecosystems support services such as pollination of crops flood regulation and water purification. These services reduce the need for costly infrastructure and chemical inputs. Recreational and cultural values of connected natural places attract tourism and enhance human wellbeing. Investing in connectivity is often cost effective when compared to repeated reactive management after declines occur.

Measuring Success and Adaptive Management

Successful connectivity projects include clear goals measurable indicators and monitoring plans. Indicators might include frequency of movement events species occupancy rates or genetic diversity metrics. Adaptive management uses monitoring information to refine actions over time. This approach recognizes that connectivity interventions may need adjustments as new data become available or as environmental conditions change.

How Individuals Can Help

People can support connectivity in many ways. Land stewards can adopt wildlife friendly practices and join local conservation agreements. Citizens can support policies that incorporate connectivity into land use planning. Volunteers can assist with habitat restoration and monitoring. For broader resources and ideas about nature conservation visit bionaturevista.com where you will find articles case studies and practical tips for protecting landscapes and species.

The Path Ahead

Ecosystem Connectivity is essential for healthy resilient nature. As pressures on the natural world intensify the value of connected landscapes becomes clearer. From small community led efforts to national scale planning the goal is to keep nature linked in ways that allow life to persist adapt and flourish. By combining scientific insight sound policy and community engagement it is possible to design landscapes that sustain both biodiversity and human wellbeing.

Conclusion

Understanding and improving ecosystem connectivity is a strategic conservation priority. It preserves the movement of species supports ecological functions and strengthens resilience to change. Practical actions range from restoring habitat corridors to integrating connectivity into planning and policy. With collaborative effort and smart investment connected landscapes can become a lasting legacy that supports diverse life for future generations.