Habitat Fragmentation

What Habitat Fragmentation Means for Nature and People

Habitat Fragmentation occurs when large continuous areas of natural habitat are divided into smaller isolated patches. This process can result from human activities such as agriculture expansion, urban growth, road building and resource extraction. It can also be driven by natural events like wildfires and storms when the landscape does not recover to its prior connectivity. The result is a mosaic of habitat fragments separated by a matrix of altered land use where movement, breeding and survival become much more challenging for many species.

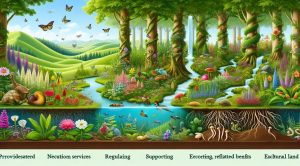

Understanding Habitat Fragmentation matters because the structure of the landscape directly shapes biodiversity health and ecosystem function. Fragmentation can reduce population sizes, increase local extinction risk and change the interactions among species. The impacts cascade from individual organisms to entire ecological communities and the services they provide to people such as pollination, water purification and carbon storage. For readers who want more articles on nature topics visit bionaturevista.com.

Key Causes of Habitat Fragmentation

There are several common drivers that lead to Habitat Fragmentation. Agricultural conversion remains a leading cause in many regions where forests, grasslands and wetlands are cleared for crops and livestock. Urban expansion and infrastructure development create long lasting barriers. Forestry practices that rely on clear cutting can fragment old growth forests. Mining and energy projects open new access into wild areas. Even low density land use when spread across a wide area can produce a permeable but still problematic matrix that isolates core habitat patches.

Climate change is an emerging amplifier of fragmentation because shifting climate zones force species to move while fragmented landscapes limit viable routes for migration. Fire regimes and invasive species can further change habitat quality and accelerate the loss of connected natural areas.

Ecological Consequences of Fragmentation

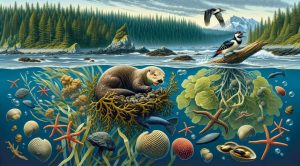

Fragmentation alters ecological dynamics in multiple ways. First it reduces the effective habitat area available to species. Smaller patches support fewer individuals and fewer species. Second it increases isolation which reduces gene flow and raises the risk of inbreeding. Third it changes edge to interior ratios. More edge area means conditions at patch boundaries such as light temperature wind and humidity become dominant and may favor common generalist species over rare specialists.

These changes often lead to simplified communities and altered food web interactions. Predators may find it easier to hunt in small patches. Pollinators may not travel between fragments which reduces plant reproduction. Some species require large territories or complex landscapes to complete their life cycle and are highly vulnerable to fragmentation. Over time the cumulative loss of species and function can degrade ecosystem resilience and reduce the ability of natural systems to recover from disturbance.

Edge Effects and Matrix Quality

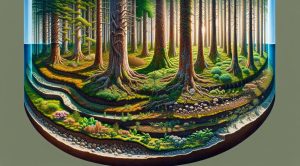

Edge effects describe the ecological changes that occur at the border between habitat and non habitat. Edges typically experience higher temperature swings more light and greater wind exposure. They are also more accessible to invasive species and human disturbance. The shape and size of fragments determine how much of their area is affected by edge conditions. Small irregular patches have a much larger proportion of edge area than compact patches with the same total area.

The matrix that surrounds fragments plays a critical role. A hostile matrix such as intensive cropland or urban sprawl presents strong barriers to movement. A benign matrix such as managed woodlands or low intensity pasture can allow many species to move and use multiple patches. Therefore conservation planning must focus not only on protecting core patches but also on improving matrix permeability to reduce the effective isolation of fragments.

Species Responses and Thresholds

Different species respond to Habitat Fragmentation in different ways. Mobile generalists often tolerate fragmented landscapes and may even expand their range. Specialist species with narrow habitat needs poor dispersal ability or strict territory requirements are most at risk. Populations often decline gradually until they cross ecological thresholds where local extinction becomes very likely. The concept of metapopulation dynamics is useful here. When networks of patches are connected by dispersal the whole system can persist even if individual patches experience local extinction. When connectivity drops below a critical threshold the rescue effect fails and biodiversity loss accelerates.

Landscape Connectivity and Wildlife Corridors

Connectivity is the backbone of any strategy to mitigate Habitat Fragmentation. Corridors and stepping stones can allow animals and plants to move across the landscape to find mates food and new habitat. Designing corridors requires knowledge of species movement behavior landscape features and the social and economic context. Linear corridors such as riparian strips and road side vegetation can be effective for many species. Wide buffer zones around protected areas increase resilience by reducing edge effects.

Connectivity planning also benefits ecosystem processes. Pollination and seed dispersal depend on movement across the landscape. Restoring connectivity can help ecosystems adapt to climate change by providing pathways for range shifts. When corridors are implemented alongside protected patches the combined effect can be greater than simply increasing the area of a reserve.

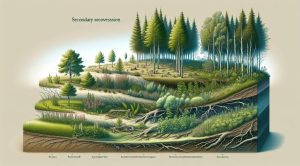

Restoration Strategies to Reverse Fragmentation

Habitat restoration can reconnect fragments and improve habitat quality. Key actions include reforestation planting native species and restoring wetlands and grasslands. Restoring structural complexity such as understory and dead wood benefits a wide range of species. Projects that create networks of small habitat patches can be highly effective in agricultural landscapes when combined with wildlife friendly practices like reduced pesticide use and hedgerow planting.

Urban restoration is another important front. Green roofs urban parks and corridors along rivers can increase permeability and provide refuges. Integrating nature based solutions into planning supports human wellbeing and biodiversity at the same time.

Policy Community and Economic Measures

Addressing Habitat Fragmentation requires policy instruments that align conservation with development. Land use planning that prioritizes a compact approach to development reduces sprawl. Incentive programs for landowners such as payments for ecosystem services and conservation easements encourage the maintenance of large connected habitats. Infrastructure planning that includes wildlife crossing structures and avoids key connectivity areas reduces fragmentation at the design stage.

Community engagement is essential. Local stakeholders from farmers to city residents benefit from healthy ecosystems and can be powerful allies. Education programs citizen science and collaborative management help build support for long term conservation measures. Market based approaches such as certification for wildlife friendly production create economic drivers for better outcomes.

Research Monitoring and Adaptive Management

Effective actions depend on evidence. Remote sensing and landscape ecology tools now make it easier to measure fragmentation patterns monitor changes and prioritize actions. Genetic studies reveal how isolation affects populations and where connectivity corridors are most needed. Adaptive management approaches that monitor results and adjust practices allow conservation efforts to improve over time and respond to new threats.

Long term monitoring is critical to detect thresholds and early warning signs of ecosystem decline. Coordinated networks of protected areas with shared monitoring yield insights that scale from local to global levels.

How Individuals Can Help

Many practical steps are within reach of individual people. Land owners can set aside natural habitat reduce mowing and plant native species. Gardeners can create small patches that act as stepping stones for pollinators. Citizens can support local conservation groups advocate for smart land use and choose products that come from wildlife friendly sources. Volunteers who plant trees monitor wildlife or help in restoration projects contribute valuable labor and build community awareness.

Digital resources and multimedia materials can help people learn and take action. For guided videos and tools that support education and outreach consider visiting Moviefil.com for relevant materials to support local projects.

Conclusion

Habitat Fragmentation is one of the most pervasive pressures on biodiversity today. Its effects ripple through ecosystems reducing species diversity altering interactions and undermining ecosystem services. The good news is that many strategies exist to reduce fragmentation improve connectivity and restore natural function. Combining sound policy local action and scientific guidance makes it possible to reverse trends and build landscapes where people and wildlife can thrive together.

Addressing fragmentation requires a landscape level perspective that balances conservation with sustainable development. By prioritizing connected networks of habitat improving matrix quality and engaging communities we can secure the long term persistence of species and the natural benefits they provide to humanity.